Podium

A Reflective Commentary.

Rosannagh Maddock, 2024

Contents

Abstract/

Quotations

Introduction

Disclaimer

Description

Sportswear and Modernity in Fashion Literature

Methods

Process

Sporting Case Studies

Inspiration from Elsewhere

Findings

Podium

Captions

Graphic Display

Discussion

The Moodboard as Play

Usage

Conclusion

Collage

Acknowledgements

Funding

Competing Interests

Data Availability Statement

References

Captions

Figures

Extended Bibliography

|

Abstract: ‘Podium’ is a series of collages made with the goal of enacting graphic fashion theory, working in a feedback loop with fashion practice, at the coalface of cultural production. These triptychs are intended to enmesh with the playful mundane, like a mirror or a map, producing an alternate perspective on sportswear and competitive activity in the embodied actions of the user, becoming a tool that the user can take with them as they make fashionable choices about how to be. Background: Fashion, sports and technology intersect in many ways and varied strengths lie in different disciplinary responses. This project was developed over three years as a practice-based PhD in collections management, with a remit to develop opportunities for public engagement with under-studied fashion and textile collections and to expand sportswear history’s interdisciplinary potential. Aims: The subject aligns with cultural trends concerned with the role that technology, fashion, speed, and competition (both formalised and spontaneous) play in contemporary society. By looking at the ways embodied time and speed have been networked together in competition, the project aims to expand conceptions of experimental fashion theory and design. Findings: A triptych of triptychs, ‘Podium’ blends ephemeral digital collections and historic sporting, film and fashion imagery in a collage process that highlights the vast potential of fashion’s popular vernacular of the ‘moodboard’ in forward-thinking research. Each panel explores a facet of success, spanning the highs and lows of achieving a celebratory podium. The result is akin to a bar graph. Discussion: Developing moodboards in complexity and utilising them in research can elaborate their potential as fields of play. Operating through automatic practices of everyday life, fashion collage is an active zone for experimentation. Conclusion: Ultimately, ‘Podium’ posits experimental fashion with graphic outputs as an exploratory practice, with the ability to anticipate cultural shifts through its dynamic, layered forms.

Summary:

· Speed and fashionability in sports culture are networked together and under-researched · ‘Podium’ provides a creative, visuals-rich research outcome in the form of nine collages · Visual/verbal collages can be a viable rapid-response format in cross-disciplinary work

Keywords: collage; fashion; sports; sportswear; technology; history; design; generative; process.

|

‘We are moving from all work to all play, a deadly game.’[1]

‘Make a map, not a tracing. […] What distinguishes the map from the tracing is that it is entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real.’[2]

‘Take William Burroughs’ cut-up method: the folding of one text onto another, which constitutes multiple and even adventitious roots (like cutting), implies a supplementary dimension to that of the text under consideration. In this supplementary dimension of folding, unity continues its spiritual labour. That is why the most resolutely fragmented work can also be presented as the Total Work or Magnum Opus.’[3]

‘… not so much a grid made from a warp and weft but more a set of figural threads behaving as complexly as those in Morris’s wallpaper designs or rugs – splitting, entangling, nesting, crossing, curling – then it becomes a field of various speeds of experience. The threads do not suddenly petrify to form a small monument of knowing, at least not in the sense of a dimensional, Euclidean jump, they remain threads, forming nodes through entangling and crossing […] it is much more a looping of feeling and memory than a shifting from feeling to knowing.’[4]

‘Salvation is no longer in flight; safety is in “running toward your death,” in “killing your death.” Safety is in the assault simply because the new ballistic vehicles make flight useless; they go faster and farther than the soldier, they catch up with him and pass him.’[5]

‘Baudelaire can still write of “a book as dazzling as an Indian handkerchief or shawl.”’[6]

Introduction

Disclaimer

If the purpose of a moodboard, as a distinct form of collage, is to produce ideas (or, more accurately, inspiration, or vibes), the ideas produced may be assessed and utilised at will. Quantitative or qualitative assessments of these ideas may be applied in different ways, coming to different conclusions, but ultimately some of these ideas may be bad ideas. The author accepts no liability for the application of said bad ideas, or any other downsides of emergent networked phenomena that arise from the work.

As the author understands fashion to be ironic in form, it is hoped that the formal and tonal experimentation in the work is understood not as parody, but as a pastiche, meant with all the affection that the term shares with collage. Certain images, concepts and forms are brought together and in the sincere incorporation of fashionable imitation, a funhouse mirroring, with the lightness and breezy remixing that such ideas entail, new possibilities are iterated.

Description

This project is the culmination of three years of in-depth interdisciplinary research. It began with an identified need to develop the field of sportswear history through the medium of visual archival research. Funding from Techne, the doctoral training partnership, was awarded in order to produce a body of work, developed out of under-utilised object- and image-based collections in museums, with a particular focus on textiles. A range of methodologies and processes were utilised over the three-year period, with graphic artworks, essays, discographies and poetry forming a portfolio of creative markers. The need for a concluding summative statement was established and ‘Podium’ is the result. A triptych of triptychs, it blends ephemeral digital collections, historic sporting imagery, film stills and fashion imagery in a collage process that highlights the vast potential of fashion’s popular vernacular of the ‘moodboard’ to contribute to complex, forward-thinking research.

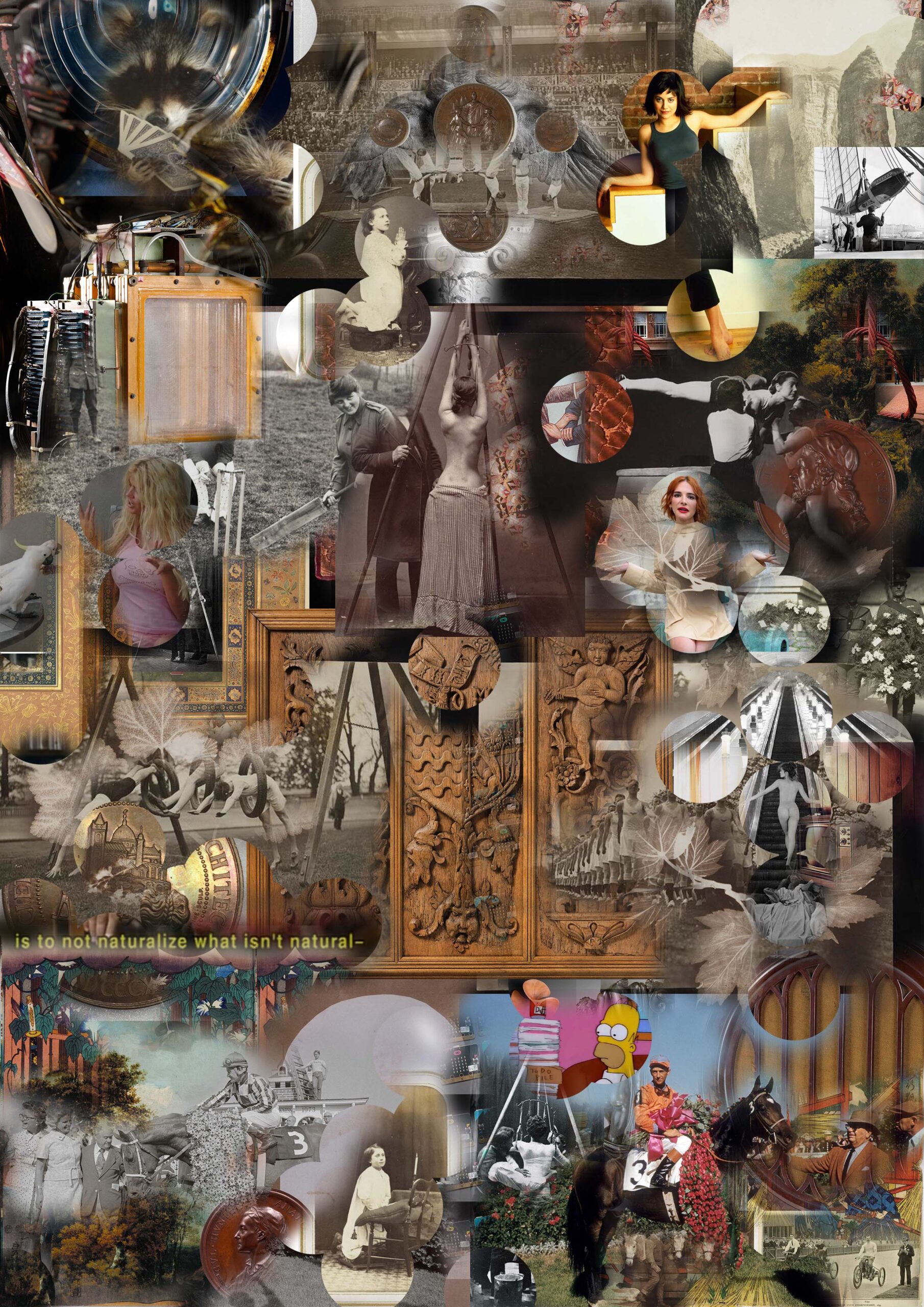

The images that constitute the raw data have been gathered through an extensive trawl of varied collections: from digitised collections held by major museums, uncatalogued archives, national library collections and stock photograph databases, to personal ephemera collections, deep-dive google searches, and movie screen grabs. Each panel is A2 in size and explores a facet of success, spanning the highs and lows of achieving the celebratory podium of many classic sports. Each panel is stacked, thematically and/or physically, vertically, one atop the other, to form a roughly six-foot block of three images. They can be presented staggered in the form of a podium, with silver, lower, on the right side of gold, and bronze, on the ‘first step’ on its left. The result is akin to a bar graph, and its statistical, data-heavy effect is an intrinsic result of rigorous processes of selection.

By taking imagery and information that would normally be consumed in linear fashion, in readily comprehensible context, and piling it upon itself, the hope is to achieve a sense of the vitality of embodied human competitive endeavour – its density and messiness. Each ‘medal’ or ‘position’ of three images was sorted according to an open-ended logic: the upper panel features triumphant themes, the centre panel technical, process-based themes, and the lower panel what can be considered the ‘downside’ of each position. As such, it forms a disrupted x-y axis of sorts, a flowing grid of perspectives and data points. Each medal is accompanied by a caption, gleaned from the written record, which highlights a story or set of data that offers a textual approach to this visually-rich collage-based research outcome.

Sportswear and Modernity in Fashion Literature

While this research is primarily centred around practical engagement with understudied fashion and sporting collections, and spins out directly from critical object and image analysis, it is surrounded by intersecting fields of active scholarship that pursue varying methodologies. The critical lens of this project overlays sports and technology histories with fashion practice, in both formal and informal frameworks, to articulate the way fashion intersects with authority to motivate people. By exploring how fashion incentivizes through glamourous behaviour and stimulating embodied practice, it is possible to trace a feedback loop and come to a fuller understanding of how modern society works with social technologies like fashion to embed speed and competitive innovation as desirable qualities. This hypothesis can be tested in a number of ways: relevant approaches and methodologies can be found across the spectrum in fashion, textiles, engineering, architecture, sports and gender studies. Popular methods include analysis of advertisements, photographs, contemporary media depictions and more traditional methods such as close reading of contemporary literature, high art, and administrative archival collections. Of particular interest here is the intellectual history of what could be termed generative design theory. As a researcher I am interested in what ideas people hold in their minds about fashion and design as they make active design interventions that have the potential to change the course of our lives and culture. Intellectual history is difficult to pin down in texts and objects can speak volumes. While many of the studies in print do not share a focus on generative process, certain intersections exist, primarily with the more theoretically-minded fashion histories.

A non-exhaustive review of these fashion studies, selected with emphasis on the canonical, can elucidate these connections: an informative survey of the topic of fashion and technology comes from Phyllis G Tortora in Dress, Fashion and Technology: From Prehistory to the Present (2015).[7] Tortora’s study gives varied detail on the relationship between technology and fashion, starting form prehistoric protective wear but structured around the core of the industrial revolution, and helps redress the differing analytic attitudes to fashion and technology, noting that works on the two subjects often do not intermix, usually speaking to separate audiences in different ways. Jennifer Craik’s book Uniforms Exposed: From Conformity to Transgression (2005) pursues the concept of the uniform as a motif that links with various themes such as work, leisure, authority and culture. It calls on extensive theoretical underpinnings to establish a sociological framework for approaching all forms of uniform. Craik’s argument stresses interdisciplinarity and the networked power of dress to underpin political reality. Concepts rooted in theory such as ‘body techniques’ are front and centre and these haptic approaches are, for Craik, a way to emphasise the ability of an embodied approach to capture the host of factors that act through uniformed dress.[8] Elizabeth Wilson’s Adorned in Dreams, a foundational text in the field, establishes groundwork on the subject of fashion and modernity. Published in 1985 and still a benchmark, Wilson approaches the subject with a blend of chronological and thematic groupings, and builds on the core texts of art-historical mid-century fashion studies while breaking new analytic ground. It is critical of non-specialist approaches to fashion but still bears the defensiveness common to much fashion writing, risking treating the subject as a special case rather than an integrated, fluid and vital part of everyone’s lives.[9] Caroline Evans’s Fashion at the Edge (2003) is alongside Wilson in terms of impact in the arena of theory-oriented fashion studies.[10] It is a densely-illustrated work with a fashion-industrial focus and highlights fashion in a vernacular that flows out of fashion as creative practice, rather than assenting to the purity of plain text. Evans emphasises the fashion-creative process, discussing ‘ragpicking’ as an active method for developing new fashion ideas, a re-mixing of material heritage, that has relevance for fashion researchers as an intellectual technique. A close focus on embodied aspects of fashion is supported by Joanne Entwistle’s The Fashioned Body (2000). It is a deep dive into the fashion-relevant aspects of Twentieth Century social theory, and is valuable as a survey of sociological concepts of dress while contributing an original emphasis on fashionable embodiment.[11] Radu Stern’s Against Fashion (2004) is a more modernist-specific study with both subject and methodological relevance; Stern presents a series of primary source texts on the subject of radical avant-garde anti-commercial dress, focusing on aesthetic dress of the late Nineteenth Century, Russian Constructivist experiments and Futurist manifestos for dress.[12] It is well-illustrated and provides valuable straight-from-the-source readings alongside brief analysis. Ulrich Lehmann’s Tigersprung: Fashion in Modernity (2000) presents a history of fashion at the height of modernity through a literary and philosophical history of ideas. Each chapter pairs a thinker, writer or school of thought (including Benjamin, Baudelaire and Simmel) with corresponding developments in fashion, and while, as with Stern’s work and studies like it, it risks placing the activities of an artistic elite in the centre, over the reality of wider society and critical questions of class and practice in intellectual history, this approach contributes a vital intermixing of dress history and the history of ideas.[13] More recently, some scholars of dress have turned towards a phenomenological examination of recreations of dress. An earlier iteration of this research, pre-2020, explored the potential of experimental dressmaking, following in the footsteps of living-history researchers like Kat Jungnickel (Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear, 2018), who dress in the garments they study as a method for gathering embodied experiential data.[14] While this approach was not practical to implement, it undoubtedly influenced this study and offers an alternative method for examining sportswear and modernity. A close relative of this project, temporally and methodologically, is the catalogue of the FIDM Museum’s exhibition Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls 1800-1960 (2021), a glossy coffee-table-style book, which contains high-quality mounted display photography, creatively staged and colourfully formatted. It is encyclopaedic in character and scope, and possesses a reference-book-orientation that demonstrates sportswear history’s cross-cultural potential.[15] All the aforementioned works share an emphasis on blending theoretical, technical and visual information with this project. As it builds on the past, dashing back-and-forth and cutting through temporal sedimentary layers, studies of fashion have the opportunity to reflect the simultaneity and mystery of the fashion process, and ‘Podium’ contributes another clue to this mystery, a gnomic navigation aid.

Methods

Process

Two approaches were employed for image sourcing, one established and habitual and the other reaching forward towards a more objective process: the first stage of data gathering for ‘Podium’ started with going through my extensive personal ephemera collections, which I collect both habitually and as a personal response to the more formal research methods also pursued. A trawl of memory sticks full of random collections of inspiring imagery from every possible source was undertaken. This is the central process in my daily output of collaged moodboard production, which works as a track record of trend forecasting for fashion practice and a personal diary. A second phase to the collecting engaged with more authoritative sources of information: a more rigorous method was pursued, with specific key search terms applied evenly across a range of online collections, selected for their scale and subject relevance.[16] This process was a creative take on the systematic review, and all applications of search terms in each collection was recorded in a spreadsheet for reproducibility.[17]

The images sourced in these two searches were sorted into three folders: films, texts, memes and fashion in the first, sports history in the second, and decorative arts images with thematically-appropriate textures (metals, colours) in the third. Each of these sections was then sorted into gold, silver and bronze. A final sweep, sorting each medal into ‘triumph’, ‘practice’ and ‘downside’ (upper, centre and lower panels), concluded this process, which lasted about five months. The collage creation process, on the other hand, was quick. Speed is key in the formation of power, effectiveness, and fashion-ability. Fashion, as a public-participation artform, is instinctive and works best when by-passing conscious deliberation – as a kind of automatic dressing – it expresses a collective subconscious, which only slowly comes to the conscious mind, filtering through later. The fashion, film, and textual imagery was formed into the first layer of grid-based, standard moodboards, in photoshop. Another layer was produced out of historic sporting imagery and sections of this were deleted with a crisp circular eraser, revealing the silliness beneath. The third layer was formed out of textural, thematic museum objects, including medals, and blended into the other two layers with a soft eraser, producing an airbrushed effect that contrasts with the clean lines of the previous layers. Fluctuations of layered textures is the result, with a graphic-novel feel.

Sporting Case Studies

The work that led to this outcome took many turns and expressed itself in many ways. The central process, however, was the creation of hybrid visual-formal case studies of sportswear garment typologies. In 2022, a large quantity of collages were made – which would constitute three full-length monographs if printed. I also produced written, essayistic components of many of the case studies, which ranged around in intellectual method, utilising economic history, technical analysis, biography and literature. The sheer heterogeneity of the work produced in 2022 and 2023, based upon archival object-analysis, oriented around a core of imagery from major museum collections of sportswear and sports history, meant a standard thesis became an increasingly impossible option in order to best reflect the scope of the research and highlight the strengths of the subject of sports and fashion – vitally embodied, visual media.

[1] Donna Haraway, Manifestly Haraway (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), p 28.

[2] Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), p. 12.

[3] Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), p. 4.

[4] Lars Spuybroek, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 115.

[5] Paul Virilio, Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986), p. 22.

[6] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 58.

[7] Phyllis G Tortora, Dress, Fashion and Technology: From Prehistory to the Present (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

[8] Jennifer Craik, Uniforms Exposed: From Conformity to Transgression (London: Bloomsbury, 2005).

[9] Elizabeth Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity (London: Virago, 1985).

[10] Caroline Evans, Fashion at the Edge (London, Yale University Press, 2003).

[11] Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000).

[12] Radu Stern, Against Fashion (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004).

[13] Ulrich Lehmann, Tigersprung: Fashion in Modernity (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000).

[14] Kat Jungnickel, Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2018).

[15] Christina Johnson & Kevin Jones, Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls 1800 to 1960 (London: Prestel, 2021).

[16] The key search terms were: podium; gold medal; first place; trophy; winner; champion; championship; record breaking; silver medal; second place; bronze medal; third place; medallist; athlete; sports; high score; team; laureate; rosette; uniform; gym; racing.

[17] Online collections searched: V&A Museum; Science Museum; National Gallery; National Portrait Gallery; British Museum; National Army Museum; Imperial War Museum; Royal Collections Trust; Wallace Collection; Tate; National Galleries Scotland; National Museums Scotland; Museum of London; Birmingham Museum; Wellcome; The Met; Wikimedia Commons; Getty; Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

[18] Elaine Showalter, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture in the Fin de Siècle (London: Virago, 1990).

[19] Katherine Carmines Mooney, Race Horse Men: How Slavery and Freedom Were Made at the Racetrack (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014); Mike Huggins, Flat Racing and British Society 1790-1914: A Social and Economic History (London: Frank Cass Publishing, 2000).

[20] Myriam Couturier, ‘Fashion on the Road (1870-1915): The Linen Duster Paradox’, Costume, 56.1 (2022), pp. 3-25, doi:10.3366/cost.2022.0216.

[21] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (London: Penguin Classics, 1974); Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art (New York: Dover Publications, 1956); Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, The Transformation of Nature in Art (New York: Angelico Press, 2016).

[22] Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).

[23] The Warburg Institute, ‘History of The Warburg Institute’, 2024 < https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/about-us/history-warburg-institute > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[24] MoMA, ‘Dada’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/dada > [accessed 24 April 2024]; MoMA, ‘Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/3771 > [accessed 24 April 2024]; Tate, ‘Artists: Jean Dubuffet’, 2024 < https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/jean-dubuffet-1035 > [accessed 24 April 2024]; Kröller-Müller Museum, ‘Jardin d’émail’, 1974 < https://krollermuller.nl/en/jean-dubuffet-jardin-d-email > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[25] MoMA, ‘Yoko Ono’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/4410 > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[26] MoMA, ‘John Baldessari’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/304 > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[27] MoMA, ‘Brian Eno’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/38770 > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[28] MoMA, ‘John Cage’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/912 > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[29] Rosannagh Maddock, ‘Design’, 2024 < https://rosannaghmaddock.co.uk/design/ > [accessed 24 April 2024].

Above: Lou Salomé, sometime girlfriend of Friedrich Nietzsche, left; Tod Sloan, infamous jockey, centre; Albert de Dion (tall) and Georges Bouton (short), pioneer motor car designers, right.

The first case study was the walking dress, popular among upper-class women of the later Nineteenth Century, and employed for a variety of physical pursuits in an increasingly active and liberated lifestyle. The gradual relaxing of the corseted silhouette apparent in these garments reflected the extremes of rational and aesthetic dress and the loose knits of the Twentieth Century.[18] The second case study was jockey silks. Jockey silks exist at the meeting point of a host of conflicting priorities. They are arguably the first famously visible and recognisable sports kit as part of their role in the first mass spectator sport. Their history is significantly under-researched and few physical examples are found in major museum collections. Jockeys were largely working class, immiserated and abused in search of racing results (through culturally enforced anorexia and alcoholism, for example). Many of the surviving examples of jockey silks in major museum collections are in fact children’s fancy dress outfits.[19] The third was the duster coat, beloved of Edwardian motorists and direct ancestor of the trench coat. The Edwardian motoring duster combines various design trends– colonial dress, wild west dusters, bush jackets, Garrick-style coachmen’s coats, shop coats and doctor’s white coats – all growing in popularity from the 1880s onwards. What connects these varied pursuits is protection in work, especially work connected to the body. It is a shorthand that anonymises bodies in public space, hence its strong association with the new, pure work of the Twentieth Century – scientists, engineers, and doctors all utilised its capacity to communicate selfless pursuit of de-personalised rationality. Each of these garment-typology deep dives can be related to each of the component parts of ‘Podium’, with gold reflecting the liberatory themes apparent in the walking dress, silver the questions of iconography and technology in horse racing, and bronze, the scale of mass team-based efforts and the structural function of triangulation expressed in the seeming rationality of the pale duster coat.[20] These case studies are supplemented by three captions, which dodge explanations of an underlying framework by providing a short biographical sketch or a series of seemingly plain-faced informational prompts. The operate like a shaggy-dog yarn or red cards. They are not designed as helpful pointers, but rather an added drawback or stumbling block, a referee’s misdirection.

Inspiration from Elsewhere

The formative methodology of this project has been the principle of object study, and objects, as case studies, have then been bolstered through visual sources including museum reference collections and fashion, sports and lifestyle ephemeral imagery. Other facets – history, philosophy, literature, film – then spool out from this central process. Two theorists who feature, but instead of shaping the overall approach literally, become more relevant in close inspection, are Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy and Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche, in his roving sloganeering as a poster boy for modernist degeneration, his energetic supremacist idealism (fomented alongside the fin-de-siècle sporting zeitgeist) and his collage-oriented textual outbursts; and Coomaraswamy, for his study of symbolism in culture from technology to folklore, particularly the wheel as a cosmic cycle and essential symbol, and his assertion of the abstract as being an outgrowth of the concrete and the image being the essential expression of philosophy: circles within circles.[21] By also plotting this work’s production process in grids, lists and granular search terms, it is hoped that a mapping-interplay occurs between Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari’s smooth and striated space – expressing the simultaneity of the montaged, recorded world of the photographic and data-driven grid as it enfolds and intertwines with the curling fronds of cyclical abundance and decay, memory and forgetting, of the fashion sphere.[22] Some appropriate neologisms: auto-archiving: affirming individual authority over the historic record in effusive selection, or not; programmatic cataloguing: making a list in an order of your own choosing, within/out new rules; digital collage: domestic, utilitarian and composed of elimination, a frame for roving network fuzz; Generative Fashion Design Theory: practice-based elaborate simplicity; mystical hybrid visual-verbal gothic vernacular architecture; utilising captions and annotations in the mode of fashion magazines (where it’s at); price on application; Aby Warburg-esque emergent ordering systems; fashion models as totemic, symbolic icons; ascetic veneration of the improvised visual grammar of the moodboard.[23]

Photomontage’s emergent visual shock is necessitated by the subject of sporting modernity, as recognised by Dada and the Futurists; Jean Dubuffet’s layered, othered, scrapings and total-world systems, as in The Busy Life (1953) and Jardin d’émail (1974), are a perennial influence.[24] Other references from the art sphere acting upon my work, and formative over the years, include process-based conceptual artists, especially those who concern themselves with coding-like methodologies and generative prompts for the purpose of inspiration and the defeat of cliché. Yoko Ono’s emphasis on the artistic practices of engagement and audience-led completion, especially in her book of instructions, Grapefruit (1964) is especially relevant.[25] John Baldessari also factors in, his influence can be seen in the disjointed, sub-metadata framing of the three captions that accompany each triptych, twists on the museum tombstone label, which give no direct information about the work whatsoever, only a cryptic sidebar.[26] Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, working as a deck of cards, game-like and oriented around active engagement with creative production, are a long-time source of process-based inspiration.[27] John Cage’s investigations into chance-based processes, especially his use of the I Ching, are present in the work, if only as a ghostly absence.[28]

I have produced many works in the past that have explored the potential of chance, randomisation and open-endedness as a means of producing work that is consciously positioned as an experimental, generative ‘first-draft’, a sketch-like, fast means of working and capturing both current trends and potential future combinations in an open field of play – contributions to the game of dressing. One piece was a digital print of a randomly selected fashion advert, blown up and sliced along the lines present in the image. These random pieces became the panels of a potential garment, with ribbons placed at the edges, again randomly, which could be tied around the body to create an open-ended, constantly shifting garment. Another, more grid-like, was a re-purposed sari with ribbons attached in rows along its length and breadth. The silk could be attached to the body in any way the wearer liked, an update on classical fashion. Another series of works were textual cut-ups: horoscopes were culled from fashion magazines, the activities suggested within were replaced with descriptions found in the captions of fashion editorials; rather than working on relationships or succeeding in their career, the reader was subject to the whims of dress, a green jacket might be anticipated for the end of the month, or a pair of shoes might play a pivotal role in a new appreciation for decisive action.[29]

While these experiments with randomised processes form a major backbone in my past work, its influence upon the current outcome is subtle: I have emphasised choice, composition and intent to a degree heretofore unseen in my creative work. This is mostly due to context and subject: the questions of supremacism, athletics, the winning mentality, and the triumph of individual will in the pursuit of excellence, seemed to demand focused, formal commitment. I selected each image intentionally for its ability to convey these principles, and arranged each layer according to a grid, where success was at the top and risk of failure, or downsides, were at the bottom. When I cut through each layer, museum objects opening onto into sports history, and sports and museums exposing a foundation of fashion and pop culture, some chance combinations occurred, but many back-and-forth decisions undercut the ‘scratch card’ aspects: I wanted to ‘win’, with a beautiful composition, so this work is notable amongst the body of my past work for its insistence on a particular way of working, a Nietzschean ‘will to power’, that forced my perspective through all the layers, letting chance remain on the backfoot, yet undeniably ever-present.

Podium: Gold, Upper Panel

Podium: Gold, Centre Panel

Podium: Gold, Lower Panel

Podium: Silver, Upper Panel

Podium: Silver, Centre Panel

Podium: Silver, Lower Panel

Podium: Bronze, Upper Panel

Podium: Bronze, Centre Panel

Podium: Bronze, Lower Panel

Podium: Gold, Caption

Podium: Silver, Caption

Podium: Bronze, Caption

Podium: Graphic Display

Discussion

The Moodboard as Play

Moodboards occupy a strange role in both the fashion industry and dispersed fashion practices among regular people. While promoted as a core process in developing fashion collections, moodboards are rarely seen outside of the intimacy of the studio, and when put on display, for example backstage at a fashion show, are considered promotional imagery and produced in a separate process, after the design development stage.[1] This mirrors the contemporary life of the fashion illustration in its present decorative emphasis. A more realistic expression of research imagery in the design process can be seen in Dior & I, the documentary produced to capture Raf Simons’ first season as Creative Director at Dior. Simons is seen leafing through ring-binders of historic imagery, compiled by his team.[2] Often, these images will be produced loose-leaf so that they can be re-applied and re-mixed with ease, pinned on boards or placed together while under consideration. This more pragmatic approach to image and trend research emphasises the fluidity of fashion’s development process. The more personal approach to mooodboarding reflects this: individual fashion practitioners, often femmes and girls, actively engaging in shopping and personal dress, will compile inspirational imagery with the help of internet content: images might be combined through platforms like Instagram, Pinterest, or Tumblr, and/or kept in folders in their personal devices as screen grabs. A notable practitioner of this on-the-ground method of trend research is the supermodel Bella Hadid: in an interview with Vogue, it is noted she ‘loves to make Keynote decks of the images that inspire her, and she makes them almost compulsively.’[3] Hadid has continued in this passionate, daily practice of making her way through the digital landscape, gathering information for her personal inspiration along the way, into her corporate activities, producing image-focussed presentations on a variety of topics for her colleagues, saying ‘I am the self-proclaimed ‘deck human’ of the business’.[4]

This incorporation of inspirational imagery into working practices and daily habits, in the life of Hadid and the many fashion producers who share her approach, in slide decks and the private non-commercial brands of social media spaces, reflects the conscious choices and inspired interruptions that constitute what Michel de Certeau theorises as ‘the practice of everyday life’; in his book of this title, de Certeau emphasises the conscious ways we move through public spaces as tactics that allow us to reclaim autonomy and private meaning in social and physical milieus that are often heavily commercialized.[5] This emphasis on the individual’s ability to re-make their environment through thoughtful re-purposing of ordinary choices is also present in the work of Georges Perec, who as an archivist and puzzle-designer, has been hugely influential upon not just my creative work but overall attitude to life, as I also work in medical archives with cataloguing metadata, using archival material as both the stuff of rent-paying and inspiration for creative endeavours. As a member of Oulipo, Perec explored the potential of programmatic generative constraints upon literary work, bringing in the principles of mathematics, computer science and systems thinking into the literary form as a tool for life. For Perec the ultimate form of this was the daily newspaper crossword; his novel A Void, written without the letter E, expresses the constraints that run through his life and work, and expresses the Oulipo movement’s concern with combining ‘the madness of the mathematician with the reasons of the poet’ through surrealist-adjacent structural experimentation.[6] His fascination with rules and games extended to a pre-occupation with the constraints of everyday life, he utilised techniques of

… classifying and schematising places and objects (such as alternative methods for the ‘art and manner of arranging one’s books’) – and he compiled lists. These ranged from a catalogue of all the different beds in which he had slept, to a detailed description of the evolution of the Rue Vilin over a 12-year period, and his notorious “Attempt at an Inventory of the Liquid and Solid Foodstuffs Ingurgitated by Me in the Course of the Year Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Four”.[7]

The Surrealist thread in the work of Perec is present in mine too, and although it has been a very long time since I practiced any automatic writing, much of my daily creative practice is automatic and habitual. I prioritise observation and ego-free collation, trying to turn off my discernment and bias at the research stage, which expresses many of the professional principles of archival science (the ‘respect de fonds’ being a core principle alongside ‘original order’, an anti-curatorial, public service-oriented stance). Considering fashion as a practice of daily life, incorporating art references but not actually working as art, I habitually collect imagery that I consider to be expressive of ‘the moment’, whatever it may be, but with especial interest in the ephemeral and that which might best express the qualities of a particular moment in time that might be forgotten, the easily-ignored detritus of commercial activity. The fashion process works well in its mindlessness, operating through the subconscious and in disposable objects and things, mattering because it does not matter. Fashion’s value as a process that does not really matter is essential to the argument made by Gilles Lipovetsky in The Empire of Fashion.[8] For Lipovetsky, fashion is an essential social technology of modernity because it abstracts and de-pressurises social relationships: by making clothing and identity more easily-exchanged and imitated, it encourages ease of movement between group and individual, allowing people to engage in playful, low-stakes experimentation with social identity. As a low-stakes endeavour, it makes life more meaningless, and facilitates large-scale urban social relations by making choices more light-hearted. For Lipovetsky, the silliness is the point, and fashion’s looseness becomes an essential grease for the modern, urban social machine, without which it would grind to a halt. This serious requirement of light-hearted play is also the central argument of Johan Huizinga in Homo Ludens, a foundational text in the study of sports.[9] Huizinga emphasises the contradiction in play: that it is simultaneously silly, meaningless and something people become utterly enthralled by, sinking effort and passion into it with complete seriousness. Such seriousness is only achievable in a specific area, the field of play, in which all the players know they are playing and can commit to the performance of another, dreamlike reality. For Huizinga, the social utility of the field of play extends all the way to traditional warfare and sacred ritual, both of which satisfy his definition of play as free and voluntary and beholden only unto itself, defying logic and rationality. Huizinga also contrasts the playful attributes of modern fashion and professional sports. In contemporary, formal sporting competitions, for Huizinga, the play element is lost as it becomes almost socially enforced by the commercial sphere. The stakes become too high. But fashion, in his conception, maintains the essential sporting qualities of lightness and make-believe. Everyone knows fashion doesn’t really matter, and this allows it to be free and playful. But sports have become industry by another means, and are no longer silly enough to express the importance of play.[10] For Huizinga, play is aesthetic, rhythmic, and ordered. Sports and fashion, at their best, are both cyclical, light-hearted and expressive of simultaneity of the formal and the informal, the serious and the silly. Rules are obsessed over and discarded or updated, the field of play is an arena for stress-relief and experimental identity formation; winners and losers are made, with consequences both important and faintly ridiculous. In play, society can make in-group and out-group choices with serious real-world consequences, but only by committing to the idea that it doesn’t really matter. In many ways, sports are fashion, and fashion is a sport: both are play. By collapsing these supposedly very different social practices onto each other, I hope ‘Podium’ has gone some way to point out the way that they interplay.

Usage

Option A: Print and cut up the pages as you deem appropriate, shuffle and distribute the pieces while on a run, as if you were a school boy on a paperchase.

Option B: Turn a print-out into confetti. Trespass an academic seminar and decorate the room whenever someone stops talking.

Option C: Lay a panel on the ground, in the countryside. Ask your local fairy gang (nicely) to play a game of Twister, using dungeons and dragons’ dice and the colours of the sunset/sunrise as prompts. Make the winner your king.

Option D: Make it into a hat. If you do not have a head, don’t worry. Photoshop the hat onto pictures of celebrities instead.

Option E: Read each panel very literally as containing data points on a graph. The centre is the core of the axis and negative and positive data are above and below. What conclusions can you draw from the data-set? Does the study have any flaws?

Option F: Find Nietzsche.

Option G: Choose a character from among the panels. An athlete, model, or animal. They can change appearance throughout. Zoom in at various points, travelling randomly throughout the panels, back and forth. Tell a story about what is happening the character, based on what is happening around them. For example, in the gold panel, Lisa Simpson threatens to kill Homer Simpson. Homer then wakes up in the real world, shocked to be among the icons of Mount Rushmore. His head is then turned into the FIFA World Cup trophy. What happens to Homer next? Will Lisa pay for her crime?

Option H: Save a copy of your preferred panel to your hard drive. Email it as an attachment instead of calling in sick to work. They’ll learn what you mean eventually.

Option I: Invent another way through. Devise new rules.

Conclusion

This project represents comprehensive interdisciplinary research into the history of sportswear through visual archival methods; it utilizes under-explored textile collections from museums and a variety of sources, including digitized archives, personal ephemera, and stock photographs. A range of creative outputs, such as graphic artworks, essays, and poetry, emerged from this work, with the culmination being the creation of ‘Podium’. This collaged triptych of triptychs juxtaposes technological ephemera, historic sporting imagery, and fashion visuals. It explores the theme of success in sports, visually representing the highs, lows, and complexities of athletic achievement through a layered, data-driven approach. Each triptych panel reflects a different aspect of success – triumph, process, and downfall – arranged to form a dynamic, disrupted grid that invites viewers to engage with the rich, multifaceted nature of competitive human endeavour, networked by fashionability. By analysing fashion’s role in formulating speed and glamour, the project situates fashion within broader social technologies. It draws on diverse methodologies, primarily a combination of object and image analysis, archival research, and intellectual history. Influenced by recent studies like the vibrant experimentalism of Jungnickel (2018) and the FIDM Museum’s Sporting Fashion (2021), as well as canonical works of fashion studies, this project contributes to the ongoing conversation about the dynamic, multifaceted nature of fashion and its critical role as embodied exploration in modern culture.

The first phase of image research involved sourcing images from ephemera collections and memory sticks, which serve as a personal trend diary in fashion practice. The second phase applied a more rigorous method, utilizing key search terms across online collections and drawing on authoritative sources. Images were sorted into three categories: fashion/text, sports history, and decorative arts, before each being sorted into ‘gold,’ ‘silver,’ and ‘bronze’ based on thematic relevance. A final layer of creative categorization loosely divided the images into ‘triumph,’ ‘practice,’ and ‘downside.’ The collage creation process, characterized by speed and instinct, blended these images into a grid-based moodboard format. The resulting work reflects fluctuations in texture and tone, producing a dynamic, data-rich composition. Prior to the culminating work of ‘Podium’, a vast quantity of collages and written case studies were produced, blending intellectual methods such as economic history, biography, and technical analysis. These were oriented around three case studies. The first case study focused on the walking dress, exploring its role in the evolution in women’s daily dress to a more loosened silhouette. The second case study examined jockey silks, highlighting their under-researched history as the first recognisable sports kit, thoroughly entangled with class and bodily control. The third case study looked at the duster coat, tracing its varied design origins and association with the professional, depersonalised rationality of the sciences, and its use by the Edwardian motorist. These case studies align with the thematic structure of ‘Podium’, with each medal exploring key aspects of the garments’ cultural significance. Supplementary captions further complicate the narrative, offering playful potential clues rather than direct explanations.

The personal, digital approach to moodboarding, exemplified by Bella Hadid’s compulsive image collection, mirrors Michel de Certeau’s concept of reclaiming autonomy through everyday practices. This is extended through the work of Georges Perec, whose emphasis on structure and categorization influences the creative method of collecting and cataloguing. The project draws upon Surrealist influences and prioritizes subconscious collection, reflecting the ephemeral, low-stakes nature of fashion. This aligns with Gilles Lipovetsky’s view of fashion as a social technology of modernity, encouraging playful identity exploration. Echoing Johan Huizinga’s theory of play, it affirms the ways that both fashion and sports, as forms of social play, thrive in their meaningless seriousness, where rules are an ongoing group project, and identity can be won.

The textual components of the collage work interweave multiple reflections on the relationship between fashion, movement, and artistic processes, which produces a focus on collage as a conceptual framework for organising growing thoughts. This approach to collage emphasizes non-linear connections, fragmentation, and transformation. Fashion is explored as both a fleeting and ritualistic practice, organic and inorganic, and offering a space for self-creation through continuous movement and change. The pursuit of speed, from military strategies to Marinetti’s Futurism to, highlights fashion’s connection to transience and authority. These concepts are extended through a playful yet serious engagement with artistic processes, drawing on Burroughs-esque cut-up method and Perecian emphasis on structure. By engaging with textile collections, archival research, and image analysis, the project considers fashion’s role as a tool for developing innovation as a social technology. It incorporates dual image-sourcing methods: personal ephemera and systematic digital categorization, resulting in a layered composition that explores the intersections of fashion, sport, and success. The research engages with garment typologies – the walking dress, jockey silks, and duster coat – by developing complex moodboards as both functional tools and personal expressions. The project also reflects upon the theories of de Certeau, Lipovetsky, and Huizinga, positioning fashion as a form of everyday play that allows for fluid, experimental aesthetic formations. Ultimately, ‘Podium’ posits experimental fashion with graphic outputs as an exploratory practice, with the ability to anticipate cultural shifts through its dynamic, layered forms.

Collage

A Collage of Texts That, Now Collaged, Form a Textual Collage on the Subject of Collage:

‘Speed has always been the advantage and the privilege of the hunter and the warrior. Racing and pursuit are the heart of all combat. There is thus a hierarchy of speeds to be found in the history of societies…’[11]

‘Speed as pure idea without content comes from the sea like Venus, and when Marinetti cries that the universe has been enriched by a new beauty, the beauty of speed, and opposes the race car to the Winged Victory of Samothrace, he forgets that he is really talking about the same esthetic: the esthetic of the transport engine.’[12]

‘A kindred problem arose with the advent of new velocities, which gave life an altered rhythm. This latter, too, was first tried out, as it were, in a spirit of play. The loop-the-loop came on the scene, and Parisians seized on this entertainment with a frenzy. A chronicler notes around 1810 that a lady squandered 75 francs in one evening at the Parc de Montsouris, where at the time you could ride those looping cars.’[13]

‘Around 1870 Colonal Delair notes: “Every fortress must possess a certain particular state, a certain power of resistance, which in men is called good health. In peacetime, we officers of the engineering corps are responsible for keeping the fortress in good health.” And a bit further on: “The art of defence must constantly be in transformation; it is not exempt from the general law of this world: stasis is death.”’[14]

‘… all we know are assemblages. And the only assemblages are machinic assemblages of desire and collective assemblages of enunciation.’[15]

‘A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences and social struggles.’[16]

‘Each season brings, in its newest creations, various secret signals of things to come. Whoever understands how to read these semaphores would know in advance not only about new currents in the arts but also about new legal codes, wars, and revolutions.’[17]

‘…the question is: why does a mandrill, a bower bird, or any animal with a patterned coat make use of such elaborate rituals, extensive formalities and delicate indirectness? For a Ruskinian, the question could not be easier to answer: aesthetics is primary. For the world to work, it must rely on aesthetics. Relations cannot simply be utilitarian and functionalist, like plumbing, and physically, physiologically, or mechanically direct. Everything must take a detour… nothing is so dedicated to artificiality as an animal. Why is everything so excessively dressed up? The Darwinian answer – so the dress can be taken off – is a complete reversal of the facts. The much bigger question, of course, is: why on Earth is there so much beauty?’[18]

‘In my formulation: The eternal is in any case far more the ruffle on a dress than some idea.’[19]

Continues as ‘Quotations’ at the beginning of this text.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Fan Carter, Dean Kenning, Emily Bowles, Simon Brown and Sara Upstone at Kingston University for their guidance and feedback during the project.

Funding

This work was supported by Techne AHRC Doctoral Training Partnership.

Competing Interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon written request to the author.

Higher resolution panels and captions available at: < https://podiumproject.tumblr.com/ >

References

Benjamin, Walter, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002)

Benjamin, Walter, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969)

Carmines Mooney, Katherine, Race Horse Men: How Slavery and Freedom Were Made at the Racetrack (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014)

de Certeau, Michel, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011)

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish, Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art (New York: Dover Publications, 1956)

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish, The Transformation of Nature in Art (New York: Angelico Press, 2016)

Couturier, Myriam, ‘Fashion on the Road (1870-1915): The Linen Duster Paradox’, Costume, 56.1 (2022), pp. 3-25, doi:10.3366/cost.2022.0216

Craik, Jennifer, Uniforms Exposed: From Conformity to Transgression (London: Bloomsbury, 2005)

Dazed, ‘Bella Hadid and the Boardroomification of Celebrity’, 2022 < https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/55212/1/bella-hadid-and-the-boardroomification-of-celebrity-kin-euphorics-interview > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix, Nomadology: The War Machine (South Pasadena, California: Semiotext(e), 1986)

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013)

Dizikes, John, Yankee Doodle Dandy: The Life and Times of Tod Sloan (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2000)

Entwistle, Joanne, The Fashioned Body (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000)

Evans, Caroline, Fashion at the Edge (London, Yale University Press, 2003)

Frieze, ‘Georges Perec: A User’s Manual: Georges Perec and the Oulipians’, 2000 < https://www.frieze.com/article/georges-perec-users-maual > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Getty, ‘Search: Moodboard Backstage’, 2024 < https://www.gettyimages.no/search/2/image?family=editorial&phrase=moodboard%20backstage&sort=best > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Haraway, Donna J., Manifestly Haraway (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2016)

Haraway, Donna J., Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2016)

Hobsbawm, Eric, Industry and Empire (London: Penguin, 1990)

Hobsbawm, Eric, The Age of Capital 1848-1875 (London: Abacus, 1997)

Huggins, Mike, Flat Racing and British Society 1790-1914: A Social and Economic History (London: Frank Cass Publishing, 2000)

Huizinga, Johan, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (New York: Angelico Press, 2016)

Johnson, Christina M, & Jones, Kevin L, Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls 1800 to 1960 (London: Prestel, 2021)

Jungnickel, Kat, Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2018)

Kröller-Müller Museum, ‘Jardin d’émail’, 1974 < https://krollermuller.nl/en/jean-dubuffet-jardin-d-email > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Lehmann, Ulrich, Tigersprung: Fashion in Modernity (Cambridge: MIT Press: 2000)

Lipovetsky, Gilles, The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002)

Lugli, Emanuele, The Making of Measure and the Promise of Sameness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019)

Maddock, Rosannagh, ‘Design’, 2024 < https://rosannaghmaddock.co.uk/design/ > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Maddock, Rosannagh, ‘Podium’, 2024 < https://rosannaghmaddock.co.uk/podium/ > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Maddock, Rosannagh, ‘Podium Project’, 2024 < https://podiumproject.tumblr.com/ > [accessed 24 April 2024]

MoMA, ‘Dada’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/dadaMoMa > [accessed 24 April 2024]

MoMA, ‘Brian Eno’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/38770 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

MoMA, ‘Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/3771 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

MoMA, ‘John Baldessari’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/304 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

MoMA, ‘John Cage’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/912 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

MoMA, ‘Yoko Ono’, 2024 < https://www.moma.org/artists/4410 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, (London: Penguin Classics, 1974)

Perec, Georges, A Void (London: Vintage Classics, 2008)

Prideaux, Sue, I am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche (London: Faber & Faber, 2018)

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Jennifer, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and his Ideas (London, University of Chicago Press, 2012)

Showalter, Elaine, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture in the Fin de Siècle (London: Virago, 1990)

Spuybroek, Lars, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016)

Stern, Radu, Against Fashion (Cambridge: MIT Press: 2004)

Tate, ‘Artists: Jean Dubuffet’, 2024 < https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/jean-dubuffet-1035 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Tcheng, Frédéric, Dior & I (CIM Productions, 2015)

Tortora, Phyllis G, Dress, Fashion and Technology: From Prehistory to the Present (London: Bloomsbury, 2015)

Vogue, ‘Bella From the Heart: On Health Struggles, Happiness, and Everything In Between’, 2022 < https://www.vogue.com/article/bella-hadid-cover-april-2022 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Virilio, Paul, Polar Inertia (London: Sage, 1999)

Virilio, Paul, Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986)

Virilio, Paul, The Virilio Reader, ed. James Der Derian (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998)

Warburg Institute, The, ‘History of The Warburg Institute’, 2024 < https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/about-us/history-warburg-institute > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Wilson, Elizabeth, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity (London: Virago, 1985)

Captions

Gold:

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (London: Penguin Classics, 1974)

Prideaux, Sue, I am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche (London: Faber & Faber, 2018)

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Jennifer, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and his Ideas (London, University of Chicago Press, 2012)

Silver:

Dizikes, John, Yankee Doodle Dandy: The Life and Times of Tod Sloan (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2000)

Bronze:

Hobsbawm, Eric, Industry and Empire (London: Penguin, 1990)

Hobsbawm, Eric, The Age of Capital 1848-1875 (London: Abacus, 1997)

Lugli, Emanuele, The Making of Measure and the Promise of Sameness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019)

Figures

Podium, pages 14-26: All images created by Rosannagh Maddock, 2024.

Case studies, visual examples:

Walking dress (as worn by Lou Salomé):

Prideaux, Sue, I am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche (London: Faber & Faber, 2018)

Jockey silks (as worn by Tod Sloan):

Museum of the City of New York, ‘Portrait, Tod Sloan (Jockey) on His Return from Europe’, MNY35349 < https://collections.mcny.org/CS.aspx?VP3=DamView&VBID=24UP1GQ0LVB8H&SMLS=1&RW=1276&RH=760 > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Duster coat (as worn by Georges Bouton):

Dyler, ‘De Dion-Bouton: The First European Manufacturer of Series Cars’, 2022 < https://dyler.com/blog/425/de-dion-bouton-the-first-european-manufacturer-of-series-cars > [accessed 24 April 2024]

Extended Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002)

Benjamin, Walter, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969)

Carmines Mooney, Katherine, Race Horse Men: How Slavery and Freedom Were Made at the Racetrack (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014)

de Certeau, Michel, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011)

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish, Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art (New York: Dover Publications, 1956)

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish, The Transformation of Nature in Art (New York: Angelico Press, 2016)

Craik, Jennifer, Uniforms Exposed: From Conformity to Transgression (London: Bloomsbury, 2005)

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Felix, Nomadology: The War Machine (South Pasadena, California: Semiotext(e), 1986)

Dizikes, John, Yankee Doodle Dandy: The Life and Times of Tod Sloan (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2000)

Entwistle, Joanne, The Fashioned Body (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000)

Evans, Caroline, Fashion at the Edge (London, Yale University Press, 2003)

Gilman, Sander L., Conversations with Nietzsche: A Life in the Words of his Contemporaries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987)

Haraway, Donna J., Manifestly Haraway (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2016)

Haraway, Donna J., Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2016)

Hobsbawm, Eric, The Age of Capital 1848-1875, (London: Abacus, 1997)

Hobsbawm, Eric, Industry and Empire, (London: Penguin, 1990)

Huggins, Mike, Flat Racing and British Society 1790-1914: A Social and Economic History (London: Frank Cass Publishing, 2000)

Huizinga, Johan, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (New York: Angelico Press, 2016)

Johnson, Christina M, & Jones, Kevin L, Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls 1800 to 1960 (London: Prestel, 2021)

Jungnickel, Kat, Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2018)

Lehmann, Ulrich, Tigersprung: Fashion in Modernity (Cambridge: MIT Press: 2000)

Lipovetsky, Gilles, The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy (Woodstock: Princeton University Press, 1994)

Lugli, Emanuele, The Making of Measure and the Promise of Sameness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019)

Mangan, J.A., The Games Ethic and Imperialism, (Harmondsworth: Viking, 1986)

Miller, Daniel, Stuff (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010)

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, (London: Penguin Classics, 1974)

Pastoureau, Michel, The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric, (New York; Columbia University Press, 2001)

Perec, Georges, A Void (London: Vintage Classics, 2008)

Prideaux, Sue, I am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche, (London: Faber & Faber, 2018)

Ratner-Rosenhagen, Jennifer, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and his Ideas, (London, University of Chicago Press, 2012)

Said, Edward W., Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, (London: Penguin, 1991)

Showalter, Elaine, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture in the Fin de Siècle, (London: Virago, 1990)

Spuybroek, Lars, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016)

Stern, Radu, Against Fashion (Cambridge: MIT Press: 2004)

Tosh, John, Manliness and Masculinities in Nineteenth-Century Britain, (Harlow: Pearson, 2005)

Tully, John, The Devil’s Milk, A Social History of Rubber, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011)

Veblen, Thorstein, The Theory of the Leisure Class, (London: Unwin, 1970)

Virilio, Paul, Polar Inertia (London: Sage, 1999)

Virilio, Paul, Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986)

Virilio, Paul, The Virilio Reader, ed. James Der Derian (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998)

Wilson, Elizabeth, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity (London: Virago, 1985)

[1] Getty Images, ‘Search: Moodboard Backstage’, 2024 < https://www.gettyimages.no/search/2/image?family=editorial&phrase=moodboard%20backstage&sort=best > [accessed 24 April 2024]. (I also refer to my past experience in the fashion industry).

[2] Dior & I, dir. by Frédéric Tcheng (CIM Productions, 2015).

[3] Vogue, ‘Bella From the Heart: On Health Struggles, Happiness, and Everything In Between’, 2022 < https://www.vogue.com/article/bella-hadid-cover-april-2022 > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[4] Dazed, ‘Bella Hadid and the Boardroomification of Celebrity’, 2022 < https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/55212/1/bella-hadid-and-the-boardroomification-of-celebrity-kin-euphorics-interview > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[5] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

[6] Georges Perec, A Void (London: Vintage Classics, 2008).

[7] Frieze, ‘Georges Perec: A User’s Manual: Georges Perec and the Oulipians’, 2000 < https://www.frieze.com/article/georges-perec-users-maual > [accessed 24 April 2024].

[8] Gilles Lipovetsky, The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002).

[9] Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (New York: Angelico Press, 2016).

[10] Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (New York: Angelico Press, 2016), p. 199.

[11] Paul Virilio, The Virilio Reader, ed. James Der Derian (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998), p. 24.

[12] Paul Virilio, Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986), p. 45.

[13] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 65.

[14] Paul Virilio, Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology (New York: Semiotext(e), 1986), p. 13.

[15] Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), p. 24.

[16] Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), p. 6.

[17] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 63-64.

[18] Lars Spuybroek, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p. 225.

[19] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 69.